‘Life of Pi’, Biblical Literalism and Creationism

In an Old Testament class in Seminary, we spent nearly two months talking through and studying just the first two chapters of Genesis. Seemingly straightforward, the multiple version of the story (yes, versions plural) told in those chapters are a poetic way to describe a complex history of all created things.

That class was the first time in my life that i began to get a clear understanding of the historical, cultural and literary context of the opening scenes of Genesis.

Simply put, it’s when it became ultimately clear to me that there is no possibility of a literal understanding of the creation story.

It’s not my goal in this post to offer a thorough breakdown of the original languages or give some historical background about the use of genre in scripture, but rather, to talk about the nature of storytelling and belief.

Which leads me to Life of Pi.

***[IF YOU PLAN TO SEE LIFE OF PI AND DON’T WANT SPOILERS, IT’S IN YOUR BEST INTEREST TO STOP READING NOW.]***

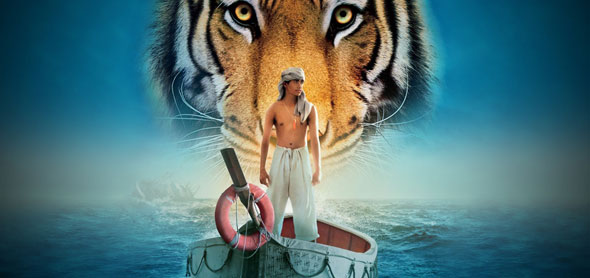

Let me be direct: Life of Pi is the best movie i’ve seen in years. Its story of dogged survival, unflinching hope and the unswerving pursuit of god made it a film that every single person should line up to see.

Whereas the movie certainly contains the aforementioned themes, it’s overarching theme, it seemed to me, is the nature of story and peoples’ capacity (or willingness) to believe (or not believe).

Long story short: a teenage boy named Pi (Piscine) escapes a pacific shipwreck (which carried his family and the animals from their zoo) in a lifeboat and finds himself floating with an injured zebra, orangutan, hyena and a bengal tiger (named Richard parker). Within the first day, the hyena kills the zebra and orangutan, followed by the tiger killing the hyena. Pi spends the next 227 days sharing a lifeboat with the tiger. (Trust me, just see it…)

When he is finally recovered, he shares his story, but no one believes him. so finally, he tells the truth: there were no animals with him on the lifeboat. Rather, there was an injured sailor (the zebra), the ship’s cook (the hyena) and his mother (the orangutan). In fact, there was no bengal tiger. The tiger is Pi himself. The cook murdered the sailor and Pi’s mother and attemtped to use them as bait for food. As an act of revenge and the fear of his own impending death, Pi murders the cook.

You see, the true story was brutal and frightening and unthinkable. People killing others and using them for fish bait. Pi witnessing the gruesome murder of his mother. And ultimately, Pi placing revenge and the will to survive over his most core values. The truth is often ugly and hard to swallow.

Stories make the truth palatable. Poetry makes the ugly beautiful. Songs make the mundane intriguing.

So it goes with the creation story. I’m a firm believer that science and scripture are wholly compatible. I believe science is right about an old Earth. And I believe science is right about evolution. I believe that it’s compatible with the accounts offered in the first 2 chapters of Genesis. If we read it correctly.

Further, I believe that the writers (and orators, since it was a culture of oral storytelling) weren’t concerned with telling a scientific story. Rather, they were concerned with telling a story to explain the origin of created things in a way that was poetic and beautiful and awe-inspiring and mysterious and culturally relevant.

Sometimes, the truth is ugly. Sometimes, it’s unbelievable. Sometimes, it’s mundane.

The creation stories in the first couple chapters of Genesis weren’t intended to be scientific accounts. They weren’t intended by the writers to be literal. That wasn’t the purpose.

They understood that poetry and evocative imagery and emotive storytelling is what endears—and even allows—belief.

The story of a boy and exotic zoo animals makes for a much more palatable and beautiful and memorable story than the facts of the darkness of the depths of the human will to survive. It’s a story more worth believing.

So may we embrace the poetry and the stories and the lavish wordsmithing of scripture, all the while embracing the reality of the evolving truths of our existence—just like Pi and his tale of bengals and belief.